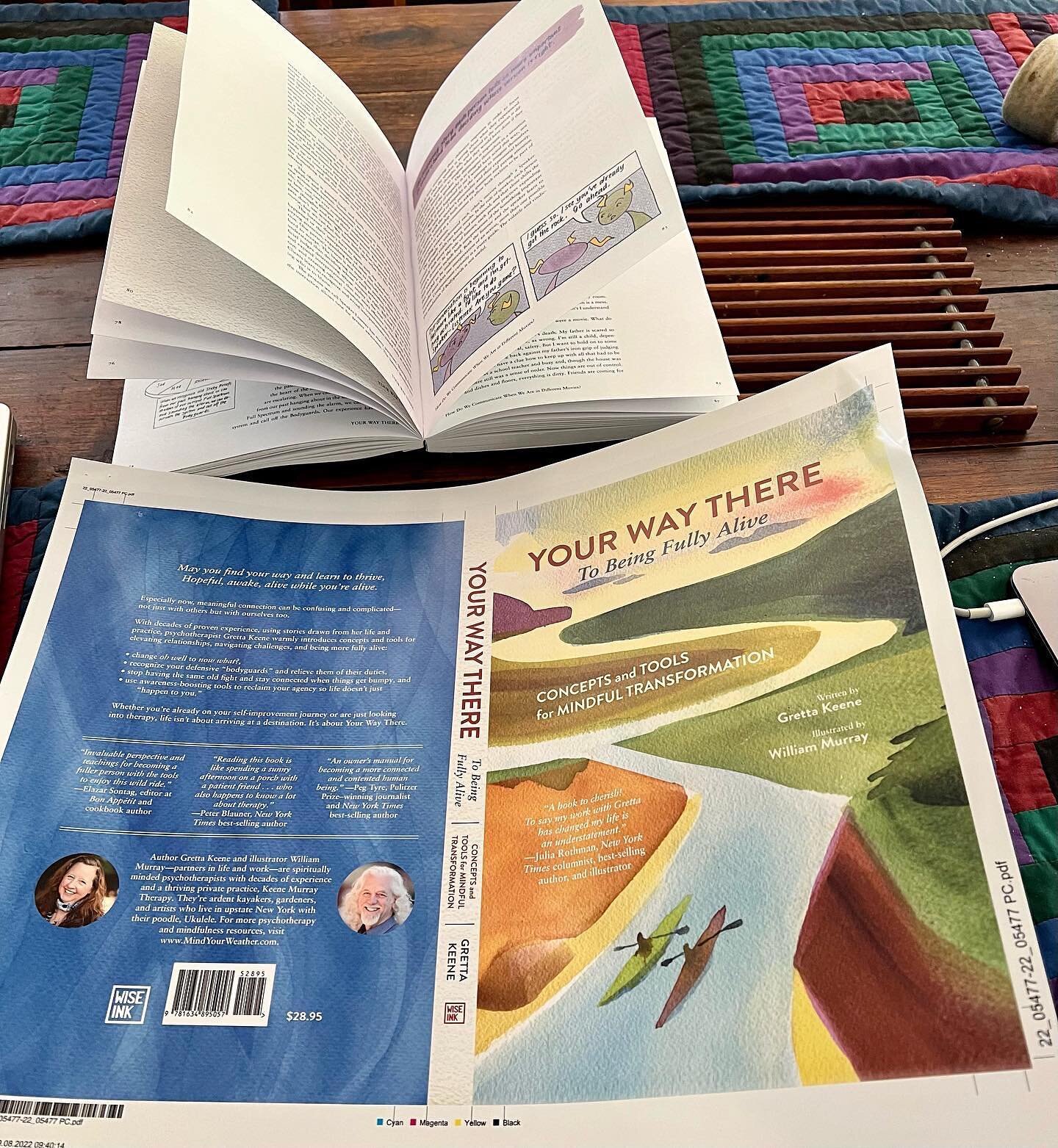

by Gretta Keene from her forthcoming book, A Practical Guide to Being Human, with illustrations by Bill Murray

People come to therapy because they are unhappy, because they are dissatisfied, because they are confused. They find that their life is not what they thought it would be, or should be, or could be. They are disappointed and uncomfortable--maybe to the point of pain. It’s a brave thing to do, to try to find the reason for our unhappiness, because people are afraid to change. In trying to change we might discover that there are no easy answers, there is no magic pill. What affects us, what males us happy or sad, hopeful or frustrated — is not external, but within ourselves. And changing ourselves is hard.

We humans tend to ignore problems and make do by sticking to what we know and to what we think others want. We muscle through without admitting that our methods for navigating our voyage through life are not effective. We kick the boat or do something to distract us from the problem, rather than look for the true cause of our troubles. What we don’t realize is that there is a hole in our boat that needs to be found and fixed, and sometimes the boat is leaking so badly we are in danger of drowning. We all need a little help sometimes.

All humans have their own unique, inner landscapes that no one else can ever completely know. As we communicate in relationships, we turn a camera on our interior world and send snapshots to those we love, hoping they will understand our inner landscape. This effort results in a greater understanding of our own complex and ever-changing network of thoughts, emotions, and filters of perception. Actions become more conscious, not just habitual reactions. The impact of our past on our present is changed by that endeavor.

My husband Bill is my best friend, fellow ardent kayaker, and partner in our psychotherapy practice. On our journey together we try to discover better ways to navigate life’s challenges and savor the joy. As therapists, we provide tools and a safe place to explore what our clients have experienced in past and present, their outer and inner adventures. The effort to understand is key.

Together and separately, Bill and I have explored many ways of exploring human existence. Personality, gender, genetics and experience formed our basic strategies. Wise teachers and their methods have influenced our paths. Hard work on our own lives and relationships has shaped our ideas and honed our techniques. Each client adds to our knowledge and expands our compassion.

The process of healing and changing is unique for each person. In our practice we act as guides, encouraging our clients to go towards what is unknown, painful or frightening – because that is also where joy and satisfaction are found. As we accompany them on their emotional expeditions, we add our observations and share useful life skills. The first step in any journey takes courage. To join courage with compassion creates the confidence for us to be curious, and this new awareness increases our ability to successfully paddle through life’s challenges. When we more effectively communicate our thoughts and feelings, and as we work to understand what others communicate, we strengthen our human connections. Through the process of psychotherapy new ways of being are practiced and internalized. People change.

ILLUSTRATION BY BILL MURRAY, PHD